Informal talks that you may have had with family members may not be specific enough for certain life-prolonging treatments to be given or withheld.

You have rights regarding your own medical care, including the right to accept or reject certain medical treatment. This may include life-prolonging procedures such as intravenous feeding or mechanical respiration. As long as you are able to communicate directly with your doctor and family members about your wishes, you can let them know what kind of treatment you do and do not want. However, if you have lost the capacity to make such decisions on your own, because you are in a coma or a persistent vegetative state, then a living will becomes important.

If you are unable to communicate during a medical emergency, your loved ones need to know whether you wish to receive emergency resuscitation to restart your lungs or heart in the event you stop breathing or go into cardiac arrest. Informal talks that you may have had with family members may not be specific enough for certain life-prolonging treatments to be given or withheld. In other cases, an individual may not have a close family member who they trust to make such decisions.

A living will addresses these uncertainties by allowing you to put your instructions regarding medical care in writing. Even if you have a close family member whom you trust to make medical decisions for you, or whom you have appointed as your health care agent, a living will allows you to give them clear instructions regarding your wishes in specific situations. If you do not have such a trusted person, then your living will provides instructions directly to your doctors and caregivers.

Issues of life and death can be difficult to face, but it is so important that you address these questions when you are healthy.

An experienced estate planning attorney can work closely with you to draft a living will that addresses the most important situations and states your wishes in such a way that they will be followed. Issues of life and death can be difficult to face, but it is important that you address these questions when you are healthy, so that your loved ones will have the guidance necessary to follow your wishes if you are incapacitated.

Questions that should be considered, in the context of a condition that leaves you incapacitated with no hope for recovery, include whether you would want:

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to restore stopped heartbeat or breathing.

- Intravenous or tube feeding or water.

- Mechanical respiration, to keep you breathing by machine.

- Your doctor to withhold treatment if the treatment would only prolong dying.

- The maximum pain relief available even if it would hasten your death.

- To donate your organs and tissues.

A living will helps to protect your wishes under all circumstances. Having a living will also helps your loved ones make difficult decisions they may otherwise be unsure of.

A living will helps protect you and your loved ones. A living will can:

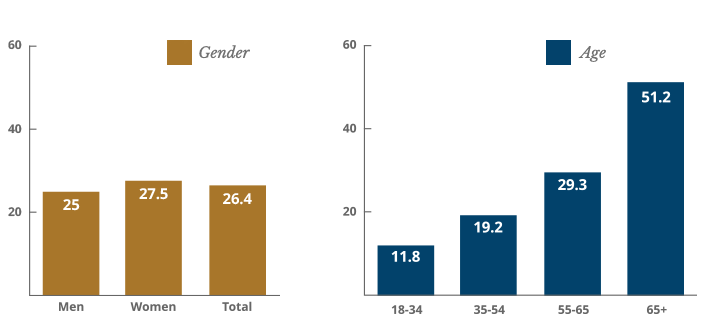

Sources: 1) The use of living wills at the end of life. A national study. View report online here.

2) Completion of Advance Directives Among U.S. Consumers, American Journal of Preventative Medicine, January 2014. View report online here.

Numbers presented as a percentage of 100.

How many Americans have a living will?

Only about one-quarter of all Americans have a living will. Analysis of reports issued in 1986 and 2014 shows that the percentage of people with a living will has not moved in nearly 30 years. People who are over 65 are most likely to have a living will.

What is a Pennsylvania Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST)?

While your instructions for your health care in the event you are incapacitated should be recorded in your living will, they may also be recorded on a specific form, which can then be filed with health care facilities. As a practical matter, the use of such forms is advisable because hospitals and doctors’ offices may be more familiar with the standardized forms, and therefore using these forms makes it easier for the medical professionals to follow your wishes. While these forms centralize certain information, they do not replace a living will or health care power of attorney.

A Pennsylvania Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form allows doctors to record your wishes regarding mechanical intervention, CPR and other treatments as a physician order. This form can then be transferred along with you from one health care environment to another.

to Appoint a Health Care Agent

If you are incapacitated, your health care agent has the obligation to make medical decisions for you according to your wishes, including your religious and moral beliefs, and in your best interest.

A durable health care power of attorney is a document that allows you to appoint someone you trust as your health care agent to make medical decisions on your behalf, in the event that you are no longer capable of making them.

What Does a Health Care Agent Do?

Your health care agent is the person you appoint to make medical decisions for you if you become incapacitated. Your health care agent’s responsibility can begin immediately if you wish, or you can state that their responsibility begins when your doctor determines that you are not able to make decisions for yourself.

If you are incapacitated, your health care agent has the obligation to make medical decisions for you according to your wishes, including your religious and moral beliefs, and in your best interest. Your health care agent may make decisions regarding whether CPR should be used to restart your heartbeat or breathing, unless you state in your health care power of attorney document that your agent cannot decide this for you. Your health care agent can also make decisions regarding intravenous or tube feeding or water, if you have communicated your wishes to your agent or written them in your health care power of attorney document.

Who Should You Trust?

Choosing a health care agent is an important matter. You will need to choose someone you trust and who will be a strong advocate for you. They need not agree with your choices, but they must agree to carry them out regardless of their own opinions. People often choose a very close loved one, such as a spouse or partner, an adult child, another relative or a friend. You cannot appoint your doctor or other health care provider as your health care agent, unless that person is a family member.

In choosing a health care agent, you should also consider the practical matter of where the person lives. There is no legal requirement that your health care agent live nearby, but in the case of a terminal illness, your health care agent may need to spend a long period of time close by in order to communicate with your doctors and make sure that your wishes are being followed. You also have the option to appoint an alternate health care agent who can take over if your first choice is unavailable or unwilling to fulfill their duties.

A durable power of attorney can help you protect your financial interests. According to the MetLife Mature Market Institute, every year seniors lose $2.9 billion to financial abuse and fraud.

Source: The MetLife Study of Elder Financial Abuse. View report online here.

A qualified estate planning attorney can assist you in drafting a health care power of attorney that properly documents your choices.

Some elements are optional, such as naming an alternate agent or stating specific instructions for your health care agent. However, the document must include certain elements, such as your name, the name of your agent, and your statement that you want your agent to be able to make medical decisions for you.

General Durable Power of Attorney

In addition to a durable power of attorney for health care, you can also designate a general durable power of attorney, which appoints someone to make legal and financial decisions for you. The document can specify that the power begins immediately, or the power can be “springing,” that is, it may be triggered by some future event, such as your inability to make decisions for yourself. The term “durable” simply means that the power continues when you are physically or mentally incapacitated. A durable power of attorney can be very specific and detailed. It may give the agent the power to pay bills and taxes, manage property, buy or sell stocks and bonds, handle lawsuits and other legal affairs, and buy or sell real estate.

Can You Change Your Mind?

Yes, Pennsylvania laws allows advance directives to be changed or revoked. You may revoke advance directives in writing or by another act that clearly shows your intent to revoke. In the most usual case, a person may wish to simply make changes, such as altering the instructions in your living will or appointing a different person to be your health care agent or alternate agent. Your estate planning attorney can assist you in making these changes.

If your advance directives are not in place, your wishes may not be followed. There are several high-profile cases that demonstrate the results of a failure to execute advance directives properly.

Too often, people put off the decision to complete advance directives for health care, in part because life and death matters can be difficult to think about, and the possibility of becoming incapacitated may seem remote. However, if you do lose the ability to make decisions for yourself, then it is too late.

If your advance directives are not in place, your wishes may not be followed. There are several high-profile cases that demonstrate the unfortunate results of a failure to execute advance directives properly.

The Terry Schiavo case is the most well-known legal struggle over end-of-life care. Schiavo was in an irreversible persistent vegetative state for 15 years, and her husband and parents disagreed over whether her feeding tube should be removed, and what Schiavo herself would want under the circumstances. Because of the lack of a living will, there was a five-year legal battle over whether life-sustaining treatment should continue.

The earlier case of Nancy Cruzan was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1990. This first “right-to-die” case supported the right of patients to refuse life-sustaining treatments, but let states decide how to regulate the circumstances under which treatment can be withdrawn when the person is incapacitated.

The case of actor Gary Coleman is an illustration of the importance of keeping advance directives updated to make sure that they reflect your current wishes. Coleman’s living will stated that he wished to be kept alive unless he was in an irreversible coma for a period of 15 days or more. However, he had also named his ex-wife as his health care agent, and she ordered doctors to disconnect Coleman’s life support one day after he fell into a coma. He died of a brain hemorrhage. In this case, the powers of the health care agent overrode the statement made in the living will, and the fact that Coleman was no longer married to the agent made the case controversial.