The probability of such a large expense simply must be planned for. Just as we maintain savings for emergencies and insurance policies for events that may never happen, it is important to have a financial plan in place if long-term care is needed.

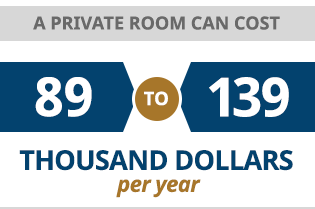

Long-term care is expensive. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the average nursing home cost is approximately $75,000 per year for a semi-private room, or $91,000 per year for a private room. Nursing home costs in Pennsylvania are higher than the national average, ranging from $89,000 to $139,000 per year for a private room, according to the Pennsylvania Health Care Association. The average person who enters a nursing home receives care for approximately three years. Other types of care, such as assisted living or home health aides, are less expensive, but still a significant cost.

How to Pay for Long-Term Care

Different families will take different approaches to planning for long-term care. About 23 percent of all long-term care expenses are paid for as out-of-pocket expenses, and some families are able to completely fund long-term care from their own resources. A small number of families purchase long-term care insurance, and about 3 percent of nursing care expenses nationwide are paid by such policies. Medicare has a limited role in paying some costs, but in general Medicare does not pay for long-term stays in nursing homes. That leaves Medicaid.

Medicaid is a crucial part of America’s health care safety net, and the program ends up covering nearly half of all nursing home costs nationwide. Medicaid has income and asset limits for eligibility, and it is the default provider for low-income families. However, with proper planning, the program can also be a safety net to help people with assets avoid having those assets depleted on the potentially devastating costs of long term care.

Medicare can cover care in a skilled nursing facility for up to 100 days if it is medically necessary for the patient to have rehabilitation services or skilled nursing. However, most care given in a nursing home is custodial care, such as help with bathing or dressing, and this is not covered by Medicare.

Most seniors have health coverage through Medicare, but that program usually does not cover long-term stays in nursing homes.

While Medicare is health insurance for older people, Medicaid is needs-based, and is generally only available to people who meet the applicable income and asset requirements. In the case of nursing home costs, Medicaid is designed to pay for long-term care once your own assets are extinguished. Certain assets, such as the home a spouse lives in and one motor vehicle, do not count toward the limits, but if your other income or assets are above the limits, you must “spend down” those amounts before you can qualify for Medicaid. However, some ways of accomplishing the spend-down are more beneficial than others.

Many people, faced with the prospect of spending down their life savings before becoming eligible for Medicaid, naturally want to preserve some assets for a spouse or the next generation. With proper planning, this can be done. However, waiting until you need long-term care will lead to problems. The Medicaid “look-back” period prevents people from simply transferring all their assets to their children and then declaring themselves to be under the asset limits. When you apply for Medicaid, any transfers of assets or gifts made within the previous five years are subject to a penalty. So while planning options to preserve assets are available even after admission into a nursing home, advance planning usually allows more assets to be protected for the family.

Pennsylvania residents with a medical need for long-term care services, whether in a nursing facility or Home and Community Based Services (HCBS), may apply for Medical Assistance online using COMPASS.

Pennsylvania residents with a medical need for long-term care services may apply for Medical Assistance online using COMPASS. This is a brief overview of the eligibility requirements:

General Eligibility

To be eligible, a person must:

- Be a Pennsylvania resident

- Be a U.S. citizen or a qualified non-citizen

- Have a Social Security number

- Have a medical need for long-term care services

Financial Eligibility

There are limits for both income and resources.

Income Limits: Most types of income are counted, including pensions, Social Security, and withdrawals from an IRA. The general income limit for Non Money Payment (NMP) Medicaid is 300 percent of the federal benefit rate (FBR), which changes from year to year.

In 2021, the FBR is $794 per month, so 300 percent of the FBR is $2,382 per month. Under Medically Needy Only (MNO) Medicaid, certain medical expenses can be deducted to reach a limit for net income.

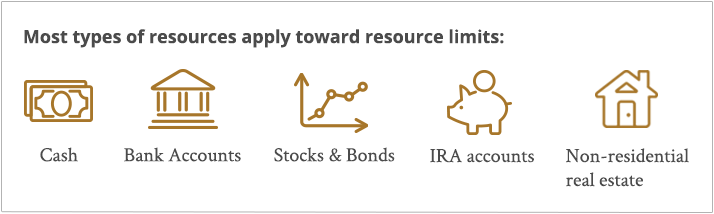

Resource Limits: Resources that are counted include: cash, bank accounts, stocks and bonds, IRA accounts, and non-resident real estate. Resources that are not counted include the home the person lives in, if the value is $525,000 or less; one motor vehicle; and burial plots and reserves, subject to certain limits.

For an individual with an income of 300 percent or less of the FBR, the resource limit is $2,000, but in Pennsylvania an additional $6,000 in resources is disregarded.

Spousal Impoverishment Rules: There are special rules that apply to married couples to protect the “community spouse,” meaning the spouse who remains in the community when the other spouse needs nursing home care. The community spouse is protected from impoverishment by allowing them to keep one-half of the couple’s total countable resources, within certain limits. In 2021, the Community Spouse Resource Allowance minimum is $26,076, and the maximum is $130,380.

Someone who anticipates a possible need for long-term care more than five years in the future may choose to transfer ownership of assets to the next generation as a sort of “early inheritance.”

There are several techniques that can be used to permit Medicaid eligibility while still preserving assets for a spouse or the next generation. It is essential that Medicaid’s complex regulations be followed precisely, as breaking the rules can result in a penalty or even a temporary ban on participation in the program.

For that reason, anyone considering these asset protection strategies should consult with an experienced elder law attorney.

Early Transfers

The first strategy is the simplest, but in many cases also the riskiest. It requires advance planning: transfer assets before the look-back period. When you apply for Medicaid, the program will examine the five-year period before the application, and assess a penalty for any gifts or transfers of assets made during that time. However, there is no penalty for gifts or transfers of assets made before the five-year period. Planning ahead, therefore, makes an enormous difference. Someone who anticipates a possible need for long-term care more than five years in the future may choose to transfer ownership of assets to the next generation as a sort of “early inheritance.” That way, if expensive long-term care is needed, the assets already transferred are protected, and the person can spend down the rest in order to meet the Medicaid eligibility requirements.

This option should not be used for any assets, such as the home, that you may need. Transfers to a child will result in the transferred assets being exposed to any marital, financial or medical problems of your child or your child’s spouse. Additionally, for assets that have appreciated significantly in value, the transfer may result in significantly higher income taxes. There are planning options that accomplish the same goal of asset protection without the risks associated with outright gifting.

Paying off a mortgage, renovating an existing home, buying household furnishings or buying a new car are all legitimate ways to spend down assets, because the home you live in and one motor vehicle are not counted toward the Medicaid limits.

Under Medicaid’s rules, excess assets must be spent down until one reaches the applicable asset limits for eligibility. However, some ways of spending those assets are more beneficial than others. If you are within the five-year “look back” period, then you cannot give your assets to a family member or transfer them for less than fair market value. However, you can use your assets to pay off existing debts or prepay large bills such as insurance premiums and real estate taxes.

Converting Assets to Income

It is often the case that a married person needs nursing home care but their spouse will continue to live in the community and will need income to live on. Annuities and reverse mortgages are two financial tools that can, under the right circumstances, provide the community spouse with income while preserving Medicaid eligibility for the spouse in the nursing home.

With a reverse mortgage, a person age 62 or older, after meeting with an approved reverse mortgage counselor, can receive a monthly payment while retaining title to the home. The loan does not become due until the last borrower dies, sells or permanently moves out of the home. Income from a reverse mortgage can be used for home expenses without being counted toward Medicaid eligibility. An annuity is a financial contract where a person pays a lump sum in return for a future income stream. A properly structured annuity can reduce resources that are counted by Medicaid, while providing an income for the community spouse, which does not count toward the Medicaid income limits. Both reverse mortgages and annuities are complex financial arrangements that must be structured properly in order to adhere to Medicaid regulations.

Medicaid rules are a complex web of interrelated federal and state regulations. Planning options are available even after admission into a nursing facility, but the earlier you plan, the better protected you, your spouse and your children will be. Consult with an attorney before using these strategies.